Friday, March 19, 2010

An amazing distribution of scores

The title of that course, was “Introduction to sociology”! Are his students extremely weak? Or is he an autocratic teacher? I don’t know. Perhaps none of them, he is may be incapable of teaching sociology, as we can see most of his students has failed the exam.

By contrast, there are teachers in Iran, whose all students pass the exams with scores of more than 16 or 17. The distribution is interesting. I don’t believe that all scores must have the normal distribution, but something that has always been in my mind is the teachers’ self-confidence. Are their means of examination so accurate that leads them to giving such amazing scores?

Tuesday, March 16, 2010

The millennium of Shahnameh

Shahnameh is one of the main pillars of the Persian language. In fact, its importance is more than this. After the invasion of Arabs (about 1400 years ago) the Iranian identity was in danger of frustration. Arabs destroyed the Egyptian identity and language. They also tried to destroy the Iranian’s identity with the military power for more than two hundred years, but at last they failed to do that, because the Iranian movements recaptured the country.

Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh consists of more than 60/000 verses, narrating the epical history of Iran. One of the stories in Shahnameh in which I’m interested, is the passing of Siavash through the fire. Siavash was a Persian prince who was accused to having a sexual intercourse with his stepmother, Sudabeh. Due to the treason of Sudabeh (with whom he refused to have sex and betray his father), he was obliged to pass through the fire to show his honesty. There was a belief that the fire would not damage the innocents.

Siavash passed through the fire successfully and everyone was convicted with innocence of Siavash. Nonetheless Siavash, despite of his innocence, self-exiled himself to Turan, where he was killed by Afrasiab. At the time of leaving Iran, at the border of Iran and Touran, he stopped the horse and looked at his beautiful land and told goodbye to Iran.

Since that time, and even nowadays Iranians remember their prince, Siavash, by passing through the fire in the last Wednesday of the persian year. This day is called “Charshanbeh Souri”. Siavash is the symbol of honesty, innocence, and peacefully in the Iranian culture. Siavash refused to fight with Turan, the Iran’s enemy. Instead of fighting, he proposed to play wicket. Today, is the 1000th anniversary of Shahnameh and “Charshanbeh Souri”.

Sunday, January 24, 2010

The phoenixes of my land

The figures published by the Legal Medicine Organization of Iran show that the highest rates of suicide is affiliated to provinces in which poverty is extensively prevalent. Provinces such as Ilam, Kermanshah and Lorestan are in this category. It may be surprising that these provinces are of the most traditional provinces of Iran with the tribal culture and with the most amount of cohesion between their people.

Isn’t it a disavowal of Durkheim’s theory? I don’t think so. If we go back to few decades behind, the theory would presumably reconcile with the fact. But now, in our times, you can see a lot of young people in such traditional and tribal provinces which have been familiar with modern cultures via different media. They think in a modern way, maybe some of them have high level of education, but at the same time they are obliged to live in the traditional situation of their community.

The situation is particularly more disastrous for women. In the traditional patrimonial cultures dominating these provinces, women and girls are considered as the possessions of their husbands or fathers. A lot of articles and books have been published on these issues (eg. On the girls’ hymen) and I don’t repeat them. What it is important here, is the discrepancy between these women’s expectations and the rough reality in these communities.

The life has lost its meaning for these women. They can’t endure to be treated as slaves while they have another democratic and modern world in their minds.

In Persian literature, phoenix (‘ghoghnous’) is a firebird that:

“It has a 500 to 1,000 year life-cycle, near the end of which it builds itself a nest of twigs that then ignites; both nest and bird burn fiercely and are reduced to ashes, from which a new, young phoenix or phoenix egg arises, reborn anew to live again.”Women and girls from the least developed provinces of Iran are our nowadays phoenixes. Notice the form of suicide they choose to free themselves: self-burning! They throw themselves in the flames of fire and let their bodies to burn completely and transform to ash. Self-burning is chosen because of its tremendous impression on other people. They want to transmit a message to us by reluming themselves. Their ashes are the seeds of a better tomorrow for my land, Iran.

Thursday, January 14, 2010

In which countries is status inconsistency more prevalent?

There are a lot of controversial discussions about the consequences of status inconsistency. But in most of the literature it is accepted that this phenomenon has been appeared as a result of the modern patterns of social mobility. Almost all the writers point to the advanced countries to show the importance of the matter. They think that status inconsistency is noticeably more prevalent in advanced countries than the so-called “third world” countries.

There are a lot of controversial discussions about the consequences of status inconsistency. But in most of the literature it is accepted that this phenomenon has been appeared as a result of the modern patterns of social mobility. Almost all the writers point to the advanced countries to show the importance of the matter. They think that status inconsistency is noticeably more prevalent in advanced countries than the so-called “third world” countries.This is arisen from a narrow-minded thought that supposes the world consisting of two major parts: the modern western countries and the traditional societies of the “third world”. I have already written about it that some countries such as Iran are neither traditional nor modern. Let me leave this extremely important problem here now, I will return to it more precisely later.

For now, I want to make a very simple comparison between Iran and Canada. I have analysed the correlation between income, education and occupational prestige. The data I have used is taken from the WVS 2000.

As you can see in the preceding picture, the correlation in all the cases is higher for Canada. What does it mean? It is the the most important problem I am going to shed light on.

Thursday, December 31, 2009

The distribution of political orientations

Iranian Intellectuals’ orientations and attitudes have an essential difference with their western counterparts. The most important characteristic of the political orientations of the western intellectuals is their normal distribution. My experience of living in the Iranian society leads me to conclude that the distribution is not normal in Iran. It may be something like the graph below:

I have discussed this earlier (here) and I will not repeat it here, but I should mention that in the western transiting societies in 18th and 19th centuries there has been a unifying process which has forced most of the intellectuals to concentrate in some specific points of the spectrum. This process is modernity. In my point of view, modernity, in spite of its diversifying tendencies can also be taken into account as a process of unification. It makes no difference whether you consider it from Durkheim’s functionalist perspective as “organic solidarity” or from the critical perspective of Frankfurt School who saw it as “decline of Individuality” and developing “similarity”. As I have mentioned in the previous posts, modernity in Iran has not been a process.

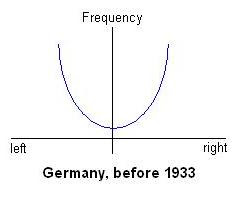

It seems that our conclusion does not apply to some western countries, such as Germany. The downfall of the Weimar Republic and rise of Nazism is precisely the consequence of the lack of normal distribution in the political orientations of German Intellectuals and people. Most of the Intellectuals (and people) were extremely right or extremely left. By 1933 the Communist Party had more than 300,000 members and the National Socialist Party had mobilized a lot of people under its flag. The society had been polarized: the communists and the Nazists.

There were little people in the “middle” to support democracy and rescue the Weimar Republic. This situation can be illustrated as below:

Of course Germany in those years was a modern society, but it was at the same time non-coherent and fragmented. Historically, the lack of social cohesion and efforts of nationalist movement to unite the society emerged the above-mentioned situation.

Of course Germany in those years was a modern society, but it was at the same time non-coherent and fragmented. Historically, the lack of social cohesion and efforts of nationalist movement to unite the society emerged the above-mentioned situation.I think this is also different from the chaotic distribution of political orientations in Iran in our times. The Iranian distribution model is not polarized, because Iran is not completely modern. The consistency of political orientations in this society is low. Moreover, the lack of solidarity in Iran is not due to the lack of historical national identity. I have pointed it earlier (here) that the national identity has maintained the Iranian society cohesive during tens of centuries and now it can still be a unifying factor. This prevents the polarization of the society.

Data Analysis

I have uses the data from World Values Survey to investigate the accuracy of this claim. The survey measures “self positioning in political scale” in a spectrum from 1 (most leftist) to 10 (most rightist). First of all I have made a comparison between Iran, United States and Canada. US and Canada have been chosen as two of the most developed and modern countries. The following graph shows this comparison.

At first glance, it seems that all of these countries have normal distribution to some extent. But if we pay more attention it will be clear that the only reason for one to think that Iran reconciles with the normal distribution pattern is the amount of respondents to item 5. Analysis of the data from other countries indicates an important point. As you can see in the graph bellow, item 5 is most chosen in all the countries.

To be continued…

Wednesday, December 2, 2009

Solidarity or Chaos

It's important to investigate a particular situation in which the divergent forces are stronger than convergent forces. In some third world countries, such as Iran, the society is partly modern and partly traditional, it may be possible that there is neither mechanical solidarity nor organic solidarity in the society. In this case there is no social cement to maintain the society cohesive. The major structures are collapsed and nothing is replaced with them. It is true that we can see some elements of modernity but it is not dominant.

This is different from what happened to western countries during their transition to modernity in 18th and 19th centuries. Their transition was gradual and steady with important changes in their epistemology which had begun from the renaissance age. In fact, the epistemological structure of European societies has changed harmonically corresponding with the other societal structures and consequently with the behaviors of the people. Any change in this road to modernity encompassed the whole society because the transition was rooted internally in that society.

In contrast, modernity was imported in some third world countries from the west. It means that we should not use the word “transition” in this case. When the western culture came to Iran, for example, a struggle began between the outsider culture, supported by intellectuals, and the aboriginal culture. But the whole society was not exposed to this outsider culture. Later, when the western media injected some western life-styles in the Iranian upper and middle class, the traditional and religious believes declined, the traditional epistemological structure collapsed but no modern epistemological structure was generated.

I name this “the epistemological crash”. Consider two huge planets crash into one another, what remains is stone fragments. These two huge planets – traditional and modern epistemological structures - no more exist, they are fractured and there will be a lot of “petite épistémês”, as I define. “petite épistémês” can’t shape the behaviors of individuals harmonically. Moreover, they have no correspondence with each other. Under such circumstances the Individuals don’t know how to think and how to act. For example we can see this in the votting behavior of Iranians, while 80% vote for reformist Khatami in 1997 and 8 years later, 80% vote for the rightist fundamentalist Ahmadinejhad in 2005.

Unlike the western countries, there is not a modern solidarity, be it called ‘organic’ or anything else - of course there is no mechanical solidarity either. The cohesion of the society is in danger.

Saturday, November 28, 2009

Eternal Iran

Iranians remain proud of their success, even in adversity. At times of civil strife and external invasion, be it Arab, Mongol, or Afghan, the Iranian state fractured but the Iranian people always remain cohesive (2).It means that in spite of unstable governments ruling in Iran, there has always been a cohesion in the society. Whether it is true or not, I think one of the most important problems for the sociologists in Iran should be the problem of cohesion. There has been a lot of chaotic periods in the Iranian history with lack of political stability. But even in these periods we can see the signs of cohesion.

The uniform identity of these people as "Iranians" during the history has precluded some events such as collapsing of the country. As the writers has mentioned:

While some Muslims may point out that Islamic civilization was at its height when Europe was engulfed in the Dark Ages, Iranians would remind them that Islamic civilization was at its height when centered in Iran (3).The aforesaid book has pointed out and passed from this extremely important issue, but I will discuss the matter of cohesion and chaos in Iran in my future posts. Nevertheless, if you want the book, just send me an email.

------------------

1- Clawson, P and Rubin, M (2005): "Eternal Iran: continuity and chaos", Middle East in focus series, Palgrave Macmillan.

2- Ibid, 159.

3- Ibid, 159.